Aby M. Warburg: Iconographer?

Introduction

Aby Moritz Warburg was a cultural historian who studied images, with the help of texts, against their historical cultural contexts. He was the eldest son of a Jewish family of bankers in Hamburg. Instead of heading the banking firm, the more usual thing to do for the eldest son, he was rooster-ed out of banking and was able to devote his time to study. With generous help from his family he laid the foundations of what later became the KBW, the "Kulturhistorische Bibliothek Warburg", in Hamburg, Germany and then the Warburg Institute in London.

Somehow, precisely how we will dive into later on, his work became seen as part of the discipline of iconography, the study of the content of works of art, via what is depicted. And that is why this chapter is part of the book you are reading. Although the incorporation of his work into the history of iconography is not wrong (seen in hindsight from the general perspective of the history of iconography), it is a bit superficial (seen from the perspective of the ideas and methods of Warburg) and it does tend to hide some of the most original and rigorous parts of his thinking and work.

This chapter will most likely prove to be a an outlier in this book, but that is because Warburg's thoughts and work, although certainly connected to it, are outliers in the field of iconography as an art historical discipline.

Biographical

Early years

Born in 1866 as the eldest son of a Hamburg banker Aby Warburg was destined, usually after taking up some apprenticeships elsewhere, to join the banking firm. He did not. It seems that he traded, at a young age [@chernow1995, p. 63], his firstborn right with his younger brother Max on the condition that Max and the firm would support him financially to pursue his research goals.

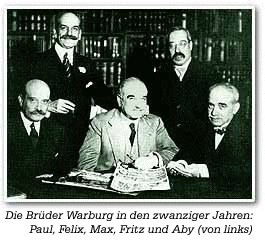

Aby Warburg, far right and his 4 brothers

A wise decision by all parties, because, as we will see later on, Aby Warburg did not enjoy a particular stable psyche: The swing between elation and gloom a bit too extreme at times.

The history of Warburg's intellectual endeavours is in a peculiar way related to the circumstances of this era. When Warburg studied in Bonn (with Hermann Usener, Karl Lamprecht, and Carl Justi ) and Strassbourg (Hubert Janitschek) in the latter part of the 19th century, the Warburgs did very well. Max Warburg, as well as the other brothers Paul and Felix, proved to be talented bankers and the Warburgs, as well as other successful Jewish families, seemed to become fully accepted as German citizens. However, the First World-War (1914-1918) and its aftermath changed this movement of Jewish emancipation dramatically.

Banking abroad

It only took two marriages to firmly establish a Warburg branch in the United States of America.

As Chernow tells the story [@chernow1995]: Sheer coincidence seems to have brought Felix and Frieda Schiff (daughter of Jacob Schiff a wealthy German-Jewish banker (Kuhn, Loeb) from New York) together as man and wife (March 1895). In 1897 Felix became a partner in the Kuhn, Loeb bank.

Aby's brother Paul married Nina Loeb in October 1895. They lived in Hamburg at first, Paul and Max working together at the bank, but he moved to the United States in 1902, also joining Kuhn, Loeb.

So, two of the five Warburg brothers, Felix and Paul, set up a stable banking bridge-head in the United States. A move that proved very important for the German firm, M.M. Warburg & Co., with Max representing Kuhn, Loeb in Germany, and also for the cultural historical branch of that firm, Aby, in the difficult years in Germany during and after the First World War.

Aby, who travelled to attend the wedding of Paul in the United States, took the opportunity to make long journeys to Arizona and New Mexico where he visited and studied Zuni and Hopi rituals.

The KBW

In 1897 Aby Warburg married a gentile woman, Mary Hertz. Together they spend much of their time in Florence where Warburg studied Renaissance art. Warburg kept on buying books. In the summer of the year 1900 he discussed the idea of a library with his brother Max [@chernow1995, p. 117]. And he went on buying a lot of books. In 1903 alone he added more than 500 books to his collection [@chernow1995, p. 117].

Warburg and his family returned to Hamburg in 1904. In 1909 the family moved into Heilwigstrasse 114.

When the number of books proved too much for a household to cope with, the Warburgs, the bankers, decided to buy Heilwigstrasse 116, thus establishing the KBW or "Kulturhistorisch Bibliothek Warburg", a private research library shaped by the research of a single man, Aby, in a city, Hamburg, that, at that time, did not have a university.

Warburg's mental breakdown, Warburg Redux, and ideas crossing the seas

Warburg became very ill in 1918 and was taken into the care of the psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger in Kreuzlingen in Switzerland in 1919.

Many doubted whether Aby Warburg would be able to recover from his illness. But in 1924 he succeeded in giving a coherent lecture at Kreuzlingen about one of his earlier research topics, the serpent ritual (a topic he had come across during his journey to the United States in 1895), thus proving to his medical staff that he was able to return home and resume his research.

But during the long period of his absence, 1918/1919-1924, many things had changed. At last Hamburg got its own university. The Warburgs had appointed Fritz Saxl as librarian of the KBW and the library had opened its doors as a research library for researchers.

Among the scholars the KBW attracted were the philosopher Ernst Cassirer and the art historian Erwin Panofsky. Panofsky had moved to Hamburg at the end of 1919. In 1926 he joined the University of Hamburg as art historian. And at the KBW he found not only books, but books organised as a research instrument to tackle art historical questions as part of larger cultural historical contexts.

Together with Saxl, Panofsky wrote a study about Dürers Melancholia print (1923) and in 1930 he published his study of the theme of "Hercules am Scheidewege".

And Panofsky would become instrumental in establishing iconography, the study of the contents of works of art to provide a cultural historical interpretation of them, through his methodological essay "Zur Beschreibung und Inhaltsdeutung von Werken der bildenden Kunst" (1932).

So, during Warburgs long absence, his ideas, as expressed through his research instrument, the books, and his small collection of published studies, proved to be important. Art history got a third pillar. The study of the historical meaning of the content of images came to complement the study of the formal aspects of images ("Stilkritik") and the more philosophical study of art ("Kunsttheorie")

In 1933 the KBW was moved (forced to move) to London and became, at the end of the Second World War, part of London University. Bing and Saxl also moved, together with the books, to the United Kingdom.

Cassirer moved to Oxford, then to Sweden and the United States.

In 1935 Panofsky moved to the United States to join the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton.

The KBW had ceased to be a private research library. Which meant that Warburg could not move books around anymore to organize his research. It was Fritz Saxl1 who introduced Warburg to large black screens upon which he could pin images and texts, and reshuffle them. These black screens became Warburg's research tool during his second working period. He organised his lectures with the help of the screens and at a certain time he decided to present his earlier research in the form of an image atlas, the Mnemosyne Atlas [@gombrich1970].

During the so-called Warburg redux period, Warburg closely worked together with Gertrud Bing, his research partner. With the Mnemosyne Atlas Warburg tried to present his earlier research in a coherent way. This proved a difficult task, as we shall see later on. When Warburg became ill in 1918 his work had consisted of small detailed studies all written in German and, of course, his library, his books, the instrument to tackle his research questions.

Warburg always had a keen methodological interest in how to pursue the historical study of images and ideas, but it is not easy to get a grip on his methodology. Warburgs ideas are hidden as small, seemingly unrelated snippets in his published works (the first period until 1918) as well as in his unpublished lectures and the GB (in the second period), but they are also present in his two large undertakings: The KBW and the Mnemosyne Atlas.

Analysing Warburgs cultural historical methods, one can not but notice an uncanny resemblance between them and the man he was: the swings between despair and elation, the dark sides of human existence and the fight of reason to escape them, the need to establish distance to see things in a relevant perspective. These things, personal and historical, mint his work in a very personal way.

Which is not to say that I think that Warburg's ideas and work show all the signs of a "looney lone ranger", but that we are dealing with the ideas and work of an extremely sensitive men, who used all this sensitivity to try to comprehend and describe the ideas and works of people from the past. In this sense, Warburgs research was a personal journey, but what is often overlooked is that this journey is also characterised by scientific rigor.

I think it is precisely that part of Warburg's work, how he construed his historical opponents, that draws generation after generation of art historians with a more cultural historical bend of mind towards his work and especially towards his last and unfinished work, the Mnemosyne Atlas.

If we speak of the work of Warburg influencing the work of others, we should realize that, should this be the case, we are looking at a very particular context this influence took place, a kind of extended "vacuum":

Warburgs long period of absence from 1918/19 until 1924 during which his private research library became opened up as a research institute associated with the newly established Hamburg University;

Warburgs scattered publications until 1918 written in German, only to be published, again in German, in 1939;

The Warburg redux period from 1924 until 1929 in which he tried to present his works and ideas in a coherent way through lectures, exhibitions and the project of the Mnemosyne Atlas. All in German and to a large extent, until recently, unpublished material;

The relocation of the KBW library and researchers inspired by it, Panofsky, Saxl, Bing and others to new contexts: UK and USA.

The relatively late impact of Panofsky's theoretical essays about iconography and iconology around 1960 (1959-1962), although formulated already in 1939.

Given this peculiar context, it would be a little bit too easy to simply infer that, since Panofsky was acquainted with the KBW, and Panofsky and Warburg both used the words iconography and iconology, they both shared a common methodology and that their work can be grouped together as part of the iconographical method (in the sense of Panofsky).

I do think that the work of Warburg influenced other researchers, like Panofsky for example, but that often this influence was indirect, via the KBW, and, seen from the perspective of Warburg's ideas and work, more or less passive.

In the next part of this essay we will focus on the work of Warburg from his second working period (1924-1929), with an emphasis on the Mnemosyne Atlas, to study his ideas about writing cultural history.

Aby Warburg as an iconographer

The use of the words iconography and iconology by Warburg

The German historian Dieter Wuttke compiled a list [@wuttke1979, p. 630-633] of 23 occurrences of the words iconography (4 occurrences) and iconology (19 occurrences) in Warburg's writings from 1889 until 1928. Wuttke found 27 occurrences of the two terms in the collection of Warburg's notes (iconography: 3 and iconology 24).

What is more important is what Warburg meant by using these words. Wuttke argues convincingly that Warburg used the two concepts in an interchangeable manner. Iconology denoting, as an extension of iconography, the practice of studying works of art and all the available historical sources as (cultural) historical phenomena [or in his own words: "Betrachtung der Kunst unter geschichtlichen Gesichtpunkten"].

But, when the words iconography and iconology are seen in this broad context, they do not signal a new historical method, because, as Wuttke argues, other researchers like Wolfgang von Oettingen and Jakob Burckhardt, also used this perspective (although they do not use the words iconography or iconology in their writings).

The next question then becomes: How precisely did Warburg, given this broad context of the historical study of works of art, construct his historical opponents?

Warburgs method

Warburg had a keen methodological interest in how to study images as historical phenomena. He never systemised these thoughts in the form of a publication but a more or less fixed range of methodological elements are available, scattered throughout his work, both published and unpublished. We find the elements together for the first time in 1907 in Warburgs publication "Francesco Sassettis letztwillige Verfügung" ("The last will of Francesco Sassetti") [@warburg1932].

These elements are:

- the refusal to adhere to art historical practices of his days

- the introduction of the idea of a cultural context

- within a cultural context the subject under study is psychologically or sociologically defined

- within this frame activity is geared towards concrete historical research differentiating all that is possible within a context

- the researcher realizes that, given the issues raised above, strictly causal arguments are aimed too high, instead the historian presents his case as plausible as he possibly can.

Zum Bild das Wort

The most important adagium used by Warburg to construct a historical opponent is the famous adagium "Zum Bild das Wort" ("to the image the word"). Adherence to this adagium made Warburg into such a prolific buyer of books. But it also meant that he would dig his way through Florentine archives, studying wills, diaries as well as money ledgers, thus being able to track the travelling roads of people, goods, images and ideas.

Construction

Warburg, always a keen producer of drawings, graphs, schemes and what one could call "storyboards", realised that cultural contexts with their socio-psychological topics were constructions by the historian in order to differentiate the way persons or groups of persons dealt with (the contents of) images in the past.

For Warburg the period we now refer to as the Renaissance was a multidimensional semantic space in which persons and groups of persons, patrons and artists, had to deal with three opposing forces, that could (literally) mark the words and images they made or commissioned: the practical oriental force (with the opposites of astrology and more scientific oriented astronomy), the Italian humanistic force (that had to find its way between the Dionysian and Apollonian extremes), and the North European courtly force (realism vs idealism).

Since images were carriers of the marks they were stamped with in this multidimensional space, Warburg tried to construct a inventory of these images with the Mnemosyne Atlas, both the images and texts one had deal with (that were stamped within their context) as well as the images and texts that were produced. Or, as Warburg formulated a title for the effort of the Atlas (at half past four in the morning): "Mnemosyne. Bilderreihen zu einer kulturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtung antikisierender Ausdrucksprägung" (Which, very roughly, can be translated as: "Mnemosyne. Images for a cultural historical view of classicising expression stamping (coining)").

In Warburgs view words and images could be as much actors ("Engramme", "Mneme") in a historical context as were the persons upon whom they acted upon. Describing these processes as part of their cultural contexts was the task of the art historian as cultural historian.

There are no shortcuts

Given the contours of the methodology sketched above, there are no shortcuts to be taken in (art) history. It is all bottom up work: Getting the texts and images one needed, analysing and describing the routes they travelled, working with paintings and sculptures but also with prints and book illustrations to track the appearance, disappearance and re-appearance of particular forms and motifs, often concealed as details within larger containers. Analysing and describing their place in the semantic space constructed with the help of the models of opposite poles ["Hilfskonstruktionen"]. But always doing this in such a way that persons or groups of persons are involved.

The context of the Mnemosyne Atlas

We have a rather good view of Warburgs undertakings during his last active period, 1924-1929, due to the so-called "Geschäftsbuch" ("Scientific journal") [@michels2001] he kept with Gertrud Bing and, to a lesser extent, Fritz Saxl.

Warburg gave lectures and organised exhibitions which he often prepared with the help of the "exhibition screens":

- the Franz Boll lecture (1925)

- the Rembrandt lecture (1926)

- the exhibition for the so-called "Orientalistentag" (1926)

- the Ovid exhibition (1927)

- the exhibition for the Deutsche Museum in München (1927)

- the Hertziana lecture in Rome (1929)

- the so-called "Dokterfeier" lecture (1929)

In the Geschäftsbuch we find an entry by Saxl, dated 26 X 26 (26 October 1926), about a lecture Saxl gave in Berlin, Warburg wrote "Gehört in unseren Atlas!" ("Belongs in our atlas!").

The Mnemosyne Atlas

In the Warburg Institute in London there exist three series of photographs of the state of the Mnemosyne Atlas. Frozen moments of a project that was always changing.

The first series of photographs dates from May 1928. It is often referred to as the '1-43 series' (there were 43 screens photographed) and it contained 682 objects. The second state of the Atlas that was captured is often referred to as the 'penultimate series'. It consisted of 71 screens with 1050 objects displayed. It was the largest series photographed because the last series, the so-called '1-79 series' [@warnke2000] consists of 63 screens with 971 objects displayed.

The 1-43 series

The buildup of the screens of '1-43' series closely reflects the research themes of Warburgs research:

screens 1-4 deal with the relation between Italy and Northern Europe

screens 11-20 deal with pictorial motifs from Antiquity that Renaissance artists had to deal with, the so-called 'Pathosformel'

screens 23-35 were devoted to astrology

screens 36-40 addressed the theme of festivities

screens 41-43 deal with works from the 17th century

Bing used a similar structure for the 'Gesammelte Schriften', Warburg's collected writings, published in 1939. And when Bing wrote a memo about the Warburg Institute in it's new London setting in 1935 she used similar topics to prioritise the new works to acquire for the library:

"With regard to new acquisitions, which at times amounted to 3.000

volumes a year and should, it is hoped, keep up an average of

1.800 to 2.000, the administration is governed by two principles:

The main sections (such as astrology, Italian art and literature,

Florentine social history, festivals and theatre, humanism and

classical scholarship, Renaissance philosophy), are kept up to

date, and missing works of earlier date are supplemented"

[@bing1935].Astrology was a semantic space always present in the atlas (Boll lecture 1925, Orientalistentag exhibition 1926). Accompanied by the context of the 'Pathosformel' (Ovid exhibition 1927) and the works from the 17th century (Rembrandt lecture 1926). Taken from Warburg's earlier publications were the contexts of the relation between Italy and Northern Europe and that of festivities.

But with this flexible working medium at his disposal Warburg experienced difficulties to bring the different themes of his research together.

Some examples of the difficulties Warburg encountered follow below.

In July 1928 Warburg writes:

Tafeln (53) aufgestellt, 979 Abb. f. Mnemosyne. Schwierigkeit: die

Placierung v. Duccio [...] ("Screens (53) put

up, 979 images for Mnemosyne. Problem: the placement of Duccio")

[25 VII - 29 VII 928]The next month Warburg notes the following:

die Anordnung d. Tafeln im Saale macht (doch) ungeahnte

Schwierigkeiten innerer Art ... [VI; p. 77; 15.VIII.928] ("the

order of screens in the room presents, substantively, unforeseen

difficulties") [15 VIII 928]These kind of factual journal entries are interleaved with more methodological entries that touch upon topics as "Mneme" ("Eintritt des antikis. Mneme", "aus dem mnemischen Erbgut") and "Symbol" ("Wesen des Symbols"). And with entries that show that Warburg was putting in some hard work on the introduction for the Atlas.

Bing, Warburg, and Franz Alber in Rome

In November 1928 Warburg and Bing were in Rome, with the screens, to prepare his so-called Hertziana lecture. And things were going well according to Bing:

Sehr intensive Arbeit für den Vortrag in der Bibl. Hertziana am

19 I 29 resultierte in dem (in handwriting by Warburg: zunächst

bei Coll. Bing nur sehr bedingt) erfreulichen Bewusstsein, dass

der Atlas wirklich grosse Fortschritte gemacht hat ("hard work for

the lecture in the Hertziana library on 29 I 29 results (in

handwriting by Warburg: "however just a little with my colleague

Bing") in the happy acknowledgment that the Atlas really made

substantial progress") [23 I 29]Back in Hamburg in August 1929 Warburg notes:

Atlas ganz schön ("Atlas really beautiful") [31 VIII 929]But the next day he started again to rearrange the images on the screens:

Habe angefangen, die ganze Götterwelt auszuschneiden, um sie

zunächst kosmologisch-monströs, tragisch-griechisch,

römisch-heroisch zu ordnen als chronologisch historisches

Phänomen ("Started to cut out the whole world of the gods in

order to present them cosmological-monstrous, tragic-greek,

roman-heroic as chronologic historical phenomenon") [1 Sept. 1929]On the opposite page, Bing expressed her doubts: "Habe bedenken, möchte aber mit Ausserung warten, bis die Anlage fertig ist" ("I have my doubts but I will wait to express these until the new arrangement is finished").

On the 20th of October 1929, just a couple of days before his death on the 26th of that same month, Warburg noted the following on the state of the Atlas:

ca. 80 Gestelle mit ca. 1160 Abb. werde ca. 6 Tafeln zu

Erkenntnistheorie und Praxis d. Symbolsetzung aufstellen (A, B, C,

D ...) ("Some 80 screens on them about 1160 images. I will prepare

about 6 screens on the epistemology and practice of 'symbol

coining' (A, B, C, D ...)") [20 X 929]Work on the last series

Screen 47 of the last series of the Mnemosyne Atlas

So up to his last working days Warburg kept finding it difficult to arrange the contents of the Atlas. Partly this is due to the medium he used. Although the large screens allow for the easy arrangment of images, and were easy to take with you whilst travelling and lecturing, they were two dimensional (perhaps three dimensional when the succession of screens would indicate a kind of a timeline). But what Warburg tried to do, to enlarge the semantic space to incorporate the various smaller spaces, is not easily expressed in this, in essence, two dimensional medium. And, to complicate things further, how should the texts that belong to the Atlas be (re-)arranged?

In essence the problem is that of possible n to n relations between, often, small parts of images and other images and texts. The more topic oriented version of the Atlas, the 1-43 series, built around the research topics (semantic spaces) of Warburg showed stable groups of images but required the onlooker to make relevant jumps to other screens containing similar content appearing in another space or in a group belonging to another period.

On the other hand the "chronological historical infusion" of the Atlas, added in the later part of 1929 would make it much more difficult for the onlooker to distill repeated patterns (groups of similar items) from the material. Warburg, realising this, then started to work on the epistemological, methodological, and practical introductory screens that were not numbered, but are marked with capital letters: A, B, etc. This way he tried to frame the onlookers of the new ordering of the Atlas to be able to regroup the material that was now laid out in a more chronological way.

What we will never know for sure, is whether Warburg would stay satisfied with this new arrangement. Could one really squeeze the various smaller semantic spaces he had studied into one large coherent group? In a way that does not seem a very "Warburgian" solution.

Warburgs work consisted of constructing semantic spaces with the help of polar models. Within those spaces he seemed to differentiate endlessly: An item belongs to this group but is slightly different than the other elements of this group. Somehow, this synthesis of the material of the latter part of 1929, understandable from the point of view that Warburg wanted to present the Atlas as a book, with a sequential order of screens, sidesteps the real problem: How to present interlocking items, both images and texts, that may be part of various and sometimes related groups?

The Mnemosyne Atlas: A laboratory for the history of images

Take for example number 47:10 (All numbers refer to the publication of the last series of the Mnemosyne Atlas by Akademia Verlag [@warnke2000]). The image depicts Tobias and the Archangel Raphael, a painting from around 1495 by Francesco Botticini. Tobias has the portrait features of the son of Raffaelo Doni who commissioned the painting.

The content of the painting, Tobias and the Archangel, is shared with some other entries on the same screen: 47:11, 47:12, 47:13, 47:14, and 47:15.

The Doni family from Florence can be linked to the family tree Warburg made of the Medici / Tornabuoni family, also from Florence (A:3).

Framed by screen 47 the pictorial motif of Tobias and Raphael is connected to Judith and her helper with the head of Holofernes: 47:20, 47:21, 47:22-1, 47:23, 47:24, and 47:25.

Warburg wrote a small but moving piece about the youngest son of A. Strozzi, Matteo Strozzi. All male family members were exiled from Florence by the Medici family: GS. And the mother was urged by one of her elder sons to send her youngest son abroad. The places exiled male Strozzi family members visited (Barcelona, Bruges, etc.) are all indicated on the map of the Mediterranean (A:2).

When we have a close look at the way the garments of the Archangel are depicted, we see the so-called 'Nympha' motif or 'bewegtes Beiwerk ("moving clothing"). One of Warburgs major research themes. This motif is all over the screens of the Atlas, but here we single out 46:6, with the Nympha on the right of the fresco by Ghirlandajo for the Tornabuoni (A:3) chapel in S. Maria Novella, Florence.

For 46:6 we can draw a similar graph with edges to node A:3, etc. but with new edges to other nodes in the Atlas.

And then there is a relation between our 47:10 and the same theme on 76:1 and 76:2 by 17th century Dutch artists.

Two small nuclei from screen 47 of the Atlas; Matteo de'Strozzi refers to Warburg's text [@warburg1892]; Pathosformel to one of his major early research topics

Like a genetic researcher Warburg tried to describe and document the smallest parts and the relations between these parts of the cultural historical fabric of human pictorial expression. Bottom up. No shortcuts allowed. With rigor.

Given the number of relations, geographical diversity and span of time Warburg had to deal with, it is not a big surprise that bringing together the results of his work always seemed to end in "dumbing down". Both the medium of the screens and that of a book too shallow to get the multitude of relations across.

In conclusion

Warburg's work and ideas still inspire researchers, like they inspired researchers in the past like Saxl, Panofsky, Klibansky, Seznec, Cassirer, Heckscher, Edgar Wind and many, many others. Through the Warburg Institute, it's collection of books, it's photographic collection, and the publications the institute makes possible.

And even today, the project of the Mnemosyne Atlas lures young historians and art historians into it's spell. Thereby confronting these researchers with that essential Warburgian cultural mission: "Embrace it in frenzy or take distance and use it in it's new context".

Warburg's research, the project of the Mnemosyne Atlas included, was very much his personal research. That being the case, and given that particular context in which the supposed transfer of ideas of iconography and iconology supposedly took place, sketched above, I do not think that what is now known as iconography and/or iconology, based upon the ideas put forward by Erwin Panofsky, covers the important parts of Warburgs work and ideas. Via Panofsky's influence iconography and iconology simply became something else, elsewhere.

Gertrud Bing had, as his research assistent, a good view on Warburg's work and ideas. In an essay, entitled "A.M. Warburg" published in the Italian Edition of Warburgs 'Gesammelte Schriften' written in 1964 she writes:

Es ist nicht das erste Mal in der Geschichte der Forschung, dass

ein Autor hinter der Fülle der Verarbeitungen und

Weiterführungen seines Werkes aus dem Gesichtfeld verschwunden

ist. Will man sich damit nicht begnügen, ihn nach dem Einfluss zu

beurteilen, den er ausgeübt had, so muss man darangehen, durch

Wiederherstellung seines Textes die Quelle neu zu

erschliessen. (Which roughly translates as: "It is not the first

time in the history of science that a researcher disappears behind

the mass of adaptions or continuations of his work. If it is not

enough to judge him for his influence, then one has to dive in to

find the source through the reconstruction of his texts".)With her statement Bing refers to one of the methodological pillars of Warburgs cultural historical work: There are no shortcuts, one has to dig up textual sources time and again to be able to construct semantic spaces in which one can document (differentiate) the actual use persons or groups of persons make of images ("psycho-sociological semantic spaces"). In other words, in Warburgs methodology one can not get persons or groups of persons out of the equation. It is simply out of the question, not done. And yet, this is precisely what Panofsky did when he defined his (in)famous third level of iconographical research, iconology.

That being said, it is fascinating to see how elements of Warburgs work and ideas seem to have connections with later developments in other scientific areas.

Gombrich grasped one of the most important parts of Warburg's ideas when he wrote an article about the idea of semantic space used by the authors Osgood, Suci & Tannenbaum [@gombrich1962].

Warburgs adagium about the human condition, "Athen muss immer wieder aus Alexandrien erobert werden", resonates strongly in the important research by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky [@kahneman2011].

And there is so much more there: Ideas about collective memory, images from the past as cultural forces ('Mneme': coined with impact), the historian as a kind of director constructing a historical opponent, the constant play with fore- and background, back- and foreground. Trying out new media. Polarity as model to be able to differentiate everything in between the poles. The idea that what we call culture is a small layer of veneer underneath which lay all the primitive forces. Setting up socio-psychological semantic spaces filled with interlocking multi-dimensional graphs (the Atlas).

But above all, there is a scientific rigor there that is unheard of in art history. Take for example the small image that depicts two small nuclei from screen 47 of the last series of the Atlas. It was generated with the Graphviz program using the so-called dot notation. Part of the structure of this file is like this:

digraph 47 {

node [shape=record];

item1 [shape=record, label="47:10"];

item2 [shape=record, label="47:11"];

item3 [shape=record, label="47:12"];

item4 [shape=record, label="47:13"];

item5 [shape=record, label="47:14"];

item6 [shape=record, label="A:3"];

item7 [shape=record, label="47:20"];

item8 [shape=record, label="47:21"];

item9 [shape=record, label="47:22-1"];

item10 [shape=record, label="47:23"];

item11 [shape=record, label="47:24"];

item12 [shape=record, label="47:25"];

item1 -> item2;

item2 -> item3;

item3 -> item4;

item4 -> item5;

item5 -> item1;

item6 -> item1;

item7 -> item8;

item8 -> item9;

item9 -> item10;

item10 -> item11;

item11 -> item12;

item12 -> item7;

item6 -> item7;}

All nodes and edges, but once visualised we can construct graphs of smallest units within the atlas and work with them using such concepts as: symmetry, interlocking, mirroring, multiple inheritance, groups, similarity, etc. The nodes are the images and/or texts, the arrows that what the historian describes, differentiates having construed a historical opponent; the real work, so to speak. The Mnemosyne Atlas: A laboratory for cultural history.

References

Private communication with Prof. Gombrich. When I wrote my PhD on the Mnemosyne Atlas I read in the biography of Warburg by Gombrich that it was Saxl who presented Warburg with the idea of the screens. Saxl served in the Austrian army during the First World War and his unit used similar screens for communication purposes. Anyways, I could not find any physical evidence of this in the archives of the Warburg Institute, so I pestered Gombrich a bit with questions about the topic. One day I got this small note by Gombrich stating: "You ask me how I know what you can't find in the archives? I know because Saxl told me so." Ok, that settled it.↩